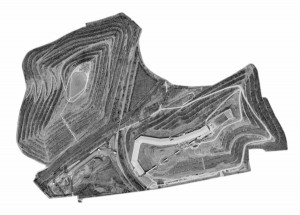

traumatized landscapes – abandoned coal mines

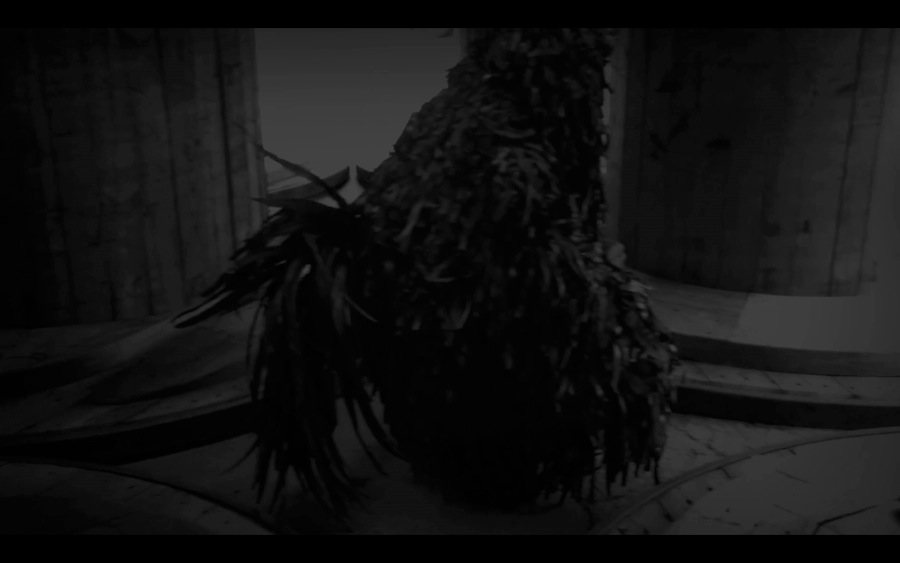

clandestine performance at the entrance of a former coalmine

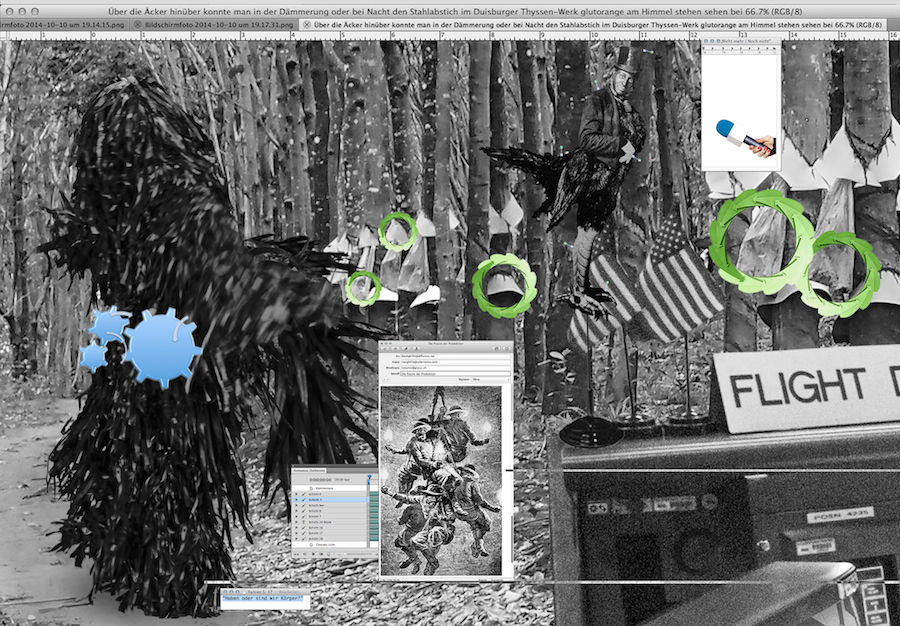

collective performance with dancers commenting the traumatized coal mine landscape

online cartography, activate link>>>> battle the landscape

protocols of incommensurable landscapes

a performative field of urban investigation in Mülheim an der Ruhr, a landscape fully eroded and traumatized by coal mining

– the dances of local adolescents with African migration background, enacting postfordistic forms of life as street art dancers, reconnecting aggressive krumping dance style from L.A. with azonto from Ghana and congolese shakalewa

– the costume of a postcolonial, black on black(face) minstrel figur, used by the vaudeville entertainer Bert William, appropriating critically rassistic stereotypes at times of Harlem Renaissance

– a voice evoking the subterraneous, in-ground landscape

[audio:https://archive.knowbotiq.net/blackghillie/joana/interviewruhrgebiet2spur mix.mp3|titles=voice]

Online cartography and liv e performance/urban intervention in Mülheim an der Ruhr, 2013

e performance/urban intervention in Mülheim an der Ruhr, 2013

credits: knowbotiq in collaboration with Idrissa Aponda + Random Boi (dance) + Gurl aka Rock, Joana Aderi (sound), Heinz Auberg (interview), B. Stork (Photo), Holger Bergmann

produced with Ringlockschuppen Mülheim, Institute of Contemporary Art Research Zürich

Protocols from the In-between Landscape

knowbotiq initiated in the context of the project Ruhr Laboratory -Precarious Landscapes 2013 research walkabouts together with street art dancers, miners and fictive figures through the meanwhile almost completely vacant coal mining towns in Germany’s Ruhr region. Participants wandered physically and imaginarily through immensely hollowed out vertical landscapes, came across the eruptive local history of Ruhr venture capital, drifted over maps drawn by overseers and seismologists, diagrammatically conceived vistas and invisible dances. The project battle the landscape! developed interpretations and interconnections that expounded the presentness of these Ruhr landscapes as past and future assemblages: a concatenation made of ecstatic formations of geological exploitations, masculine mining fervour, post-digital algorithms and sense technologies.

The crippled coal mining industry in the Ruhr harbours the intense and accelerated history of a capitalized landscape, and now manifests as a proverbial sinkhole of knowledge. The industry shares its abrupt end with other political landscapes, such as the sixteenth-century English Commons, which were converted into private land holdings, or the model city of Fordlandia, which was abandoned in the 1940s after having been wrested from the jungles of the Amazon.

Such political landscapes unleash massive changes in society, becoming multifaceted bodies of knowledge and experience, and yet simultaneously they are manifestations of the unresolvable and unknowable: The field of the unknowable[i] is not a disconnection/inclusion of that which exists. It is rather that which remains, even after processes of analysing, profiling, categorising. It is that which cannot be appropriated. The undistinguishable, impalpable, irrepressible.

knowbotiq’s artistic knowledge production is about sensitisations to this unknowable, without aiming to transfer it into the realm of knowledge production. Instead, the project intensified traces of the opaque, the concealed, the seemingly intuited, the uncomfortable and imperilling. knowbotiq activated the politically untold, or better, the not yet fully told: the traumatised landscape with its ‘eternal burdens’ left by mining. These are the black holes of its underground, which continuously fill with groundwater and must be pumped empty with great effort, expense and present-day capital to prevent a sizeable part of this landscape from flooding into the water: atmospheres of doubt vis-à-vis processes of radical landscape restructuring wander astray through the thousands of kilometres of passageways belonging to an abandoned colliery system, ruins from the present and from the future.

Dispersed Walkabouts in the Landscape

In Mülheim an der Ruhr knowbotiq unfurled a three-part performative field of investigation, which was generated through

– the dance movements of local youth, migrants with African roots, who practice ways of life as street art dancers: they organize, for example, Afrodiziak Afro-Battles, dance competitions[ii] where they connect/mix the aggressive street dance krumping from the L.A. hip-hop scene with club dances from Ghana (azonto) and the Congo (shakalewa).

– a figure created by knowbotiq named BlackGhillie, based on a dark, amorphous bodysuit/costume with a rooster tail. The rooster tail referred to the hybrid costume of a post-colonial ‘black-on-black(face)’ minstrel figure developed by the entertainer Bert Williams, who during the times of the Harlem Renaissance (1920s) critically examined dominant racist stereotypes by means of appropriation. The figure BlackGhillie was made available to the street art dancers to address the deserted mining landscapes anonymously in the darkness of the night through monstrous and parodic dances.

– the voice, memories and stories of a coal miner who gave years of his life as the leader of a rescue brigade for mining disasters, among other jobs, overextending his bodily and mental capacities, indeed his entire life, for industrial labour in the coal mining industry.

Various self-organized protagonists came into contact with the present-day Ruhr landscape in unannounced actions, masked as BlackGhillies. They danced at night atop the unstable underground mine entrances and minescapes of Mülheim. They attempted to take up unexpectable positions in a political landscape of the in-between by means of their dance sketches: displacements between physical and mental landscape; between the destruction, invasion and reconstruction of places and history[iii]; between the mining and steel-producing industries (Montanindustrie) and the creative industries (‘Momentan-Industrien’). Instead of falling into the trap of once again affirming linearly conceived, Post-Fordist and postcolonial narratives of progress vs. deterioration, participants tried to summon up tertiary landscapes, mobile positions of the in-between: as dancers, identical to ‘angels of history’, who, having alighted from the prognosticated migrational demographic data-landscapes, are no longer swept from the rubble of the past and into the future[iv] but are rather dancing before the factory gates in a very real way. This sort of ‘angel’ doesn’t ‘land’ anymore, like in the 1970s[v], like aliens arriving from outer space in Afrofuturistic mother ships / spaceships. They’re already on site, conceiving walkabouts amidst mine ruins, imaginary afrodiziak landscapes and social media platforms.[vi]

Precarious Landscapes

The precariousness of these landscape narratives in the Ruhr were evinced by the ruinous substrata of the mines. Although landmark art does transform (or better yet decorate?) the (waste heap) surfaces into cultural landscapes, their unfathomable subterranean expanses ought not to be thematised. The vertical dimension of this abruptly stranded landscape is observed – one could even say conjured – only seismologically, using mere technological and geophysical methods. The frequently occurring small earthquakes and geological decompressions are recorded, marked and banished as thoroughly as possible to the scenic unconscious. Only an intentionally very imprecise information system[vii] outwardly claims to enlighten citizens about these ‘perils from the underground’.

The specific landscape of the Ruhr with its under and overground ruins of the past and future presented itself to knowbotiq as a multifaceted spatial in/justice[viii] in which narratives (that diverge from the success story of the region’s structural transformation) are not supposed to occupy any space. The stories of the hollow underground, of the innumerable Polish and Turkish migrants working the pits in the last two centuries, of the youth in the street dance scene, who are coming to the Ruhr since the mid 1990s as political refugees – none of these narratives are supposed to take an active part in this political geography. No markings ought to bear witness to their movements throughout the landscape – and yet the BlackGhillies’ dancerly and parodic walkabouts alluded obscure entryways to these absent and present ruins:

‘The Rasquache spatial imaginary is a composition, a resourceful admixture, a mash-up imagination that says, I’m here.’[ix]

battle the landscape!, knowbotiq, Mülheim an der Ruhr, 2013

diagrams, blog, live-performances, dance videos, workshops

diagram: http://blackghillie.knowbotiq.net/

participants: dancers: Idrissa Aponda, Random Boi und Gurl Wave aka Rock

sound: Joana Aderi programing website: Christoph Stähli

thanks to: Katja Assmann, Heinz Auberg, Volker Bandelow, Jochen Becker, Marc Becker, Anne Bentgens, Holger Bergmann, Andreas Broeckmann, Wolfgang Friederich, Felizitas Kleine, Jürgen Krusche, Astrid Kusser, Frank Nadermann, Michael Thiemann

supported by: IFCAR Institute for Contemporary Art Research, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste ZHdK, Urbane Künste Ruhr und Ringlockschuppen e.V. Mülheim, Institut für Geologie, Mineralogie und Geophysik der Ruhr-Universität Bochum

[i] Godfried Engbersen, ‘The Unknown City’, Berkeley Journal of Sociology Vol. 40 (1995–1996), p. 87–111

[ii] See https://www.facebook.com/events/466548406762694/?fref=ts.

[iii] David Harvey, Spaces of Capital, Routledge 2001, p.333

[iv] Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, in: Illuminations, Schocken: New York, 1969, pp. 253–264, here p. 257f.

[v] Space is the Place, Film, USA,1974. Direction: John Coney, Script: Sun Ra and Raymond Johnson, Music: Sun Ra.

[vi] These kinds of urban dances are demonstrated and performed as dance videos in highly diverse online communities worldwide, enabling the dances’ correlation with one another as well as further development.

[vii] See http://www.gdu.nrw.de/GDU_Buerger/.

[viii] Cf. Edward Soja, ‘The city and spatial justice’, 2009, retrieved from http://www.jssj.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JSSJ1-1en4.pdf.

[ix] Roberto Bedoya, ‘Spatial Justice: Rasquachification, Race and the City’, retrieved from http://creativetimereports.org/2014/09/15/spatial-justice-rasquachification-race-and-the-city/.